What I Learned from Cracking Open Crypto Copy

What Makes Great Writing? #011 - Featuring LEDGER, and the Waldorf Astoria NYC

Back when I was in corporate, we would occasionally have these unholy events called “team retreats.”

In between the scavenger hunts and free drinks, we would participate in a doomed activity:

writing a mission statement…

as a group.

This inevitably led to agony because:

Great writing does not happen by committee, and

Packing big meaning into few words is very hard.

That latter hurdle reared its head this week, as I compared two advertisements from the New York Times’ business section. The more laps I took around the language, the more marvelous it all seemed.

Aside from both being in the Times, the two ads you’re about to read couldn’t be more different.

Different product.

Different customer.

Different approach.

Contrast is a great teacher. Let’s see what we can learn.

Spotted in this analysis:

Tricolon: a phrase or sentence using three elements

Isolonon: two phrases or sentence with the same strucutre

Alliteration: repetition of the same consonant sounds

Assonance: repetition of the same vowel sounds

Parallel structure: Identical sentence structure repeated in sequence

Superlatives: an adjective that expresses the highest or a very high degree of a quality

Chiasmus: words, grammatical constructions, or concepts that are used in reverse order

The 14th Rule: Using a number in order to make a story more believable

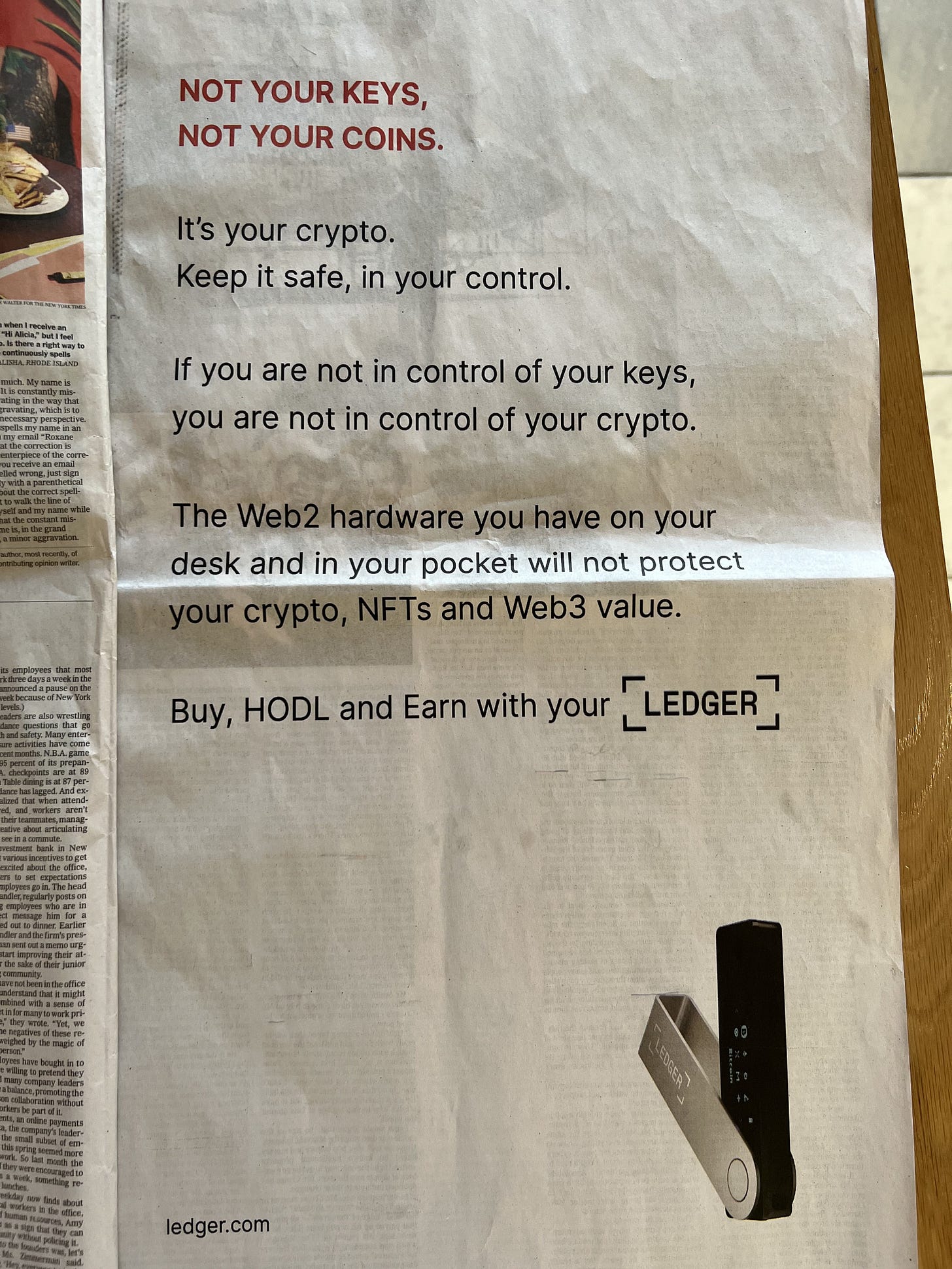

Let’s look at the whole page first.

First line: ”Not Your Keys, Not Your Coins”

Parallelism is a common tool of the ad man.

Study famous sales letters like The Two Men Who Fought in the Civil War or Tale of Two Young Men, and you’ll start to understand why.

Most ads are built to point out, dramatize, and inflame the difference between where you are now, and where you could be.

(Ian Stanley calls these two imaginary realities “Heaven Island” and “Hell Island.”)

This spot uses parallelism throughout, starting with the opening isocolon.

Notice that the writer uses the word “coins” instead of “money.” By doing so, the ad doesn’t only targeting Bitcoin enthusiasts, it cleans up the opening lines to a tidy 3-syllable meter.

(Also, there’s an alliteration in keys and coins that is ignored by the eyes, but registered by the brain.)

“It’s your crypto. Keep it safe, in your control.”

We have a chiasmus of syllables here (4-3-4), along with a smattering of alliteration - “crypto.” “keep.” “control.”

That last word is the single big idea that will drive this ad forward.

“If you are not in control of your keys, you are not in control of your crypto.”

Almost the entire ecosystem of both digital code and advertising copy is built from two words:

IF

THEN

Combined, the words create an inevitable logic, an inescapable truth. It the ultimate cause and effect phrase.

“If” here serves two purposes.

If you read the word “if,” your brain goes looking for a “then.” If writers start sentences with that two-letter atom bomb, it’s hard to stop reading. If they point it out, it’s still hard to see the pattern.

If the words in the sentence resonate with you, you now “qualify” for this product. You say “oh, I need this.”

“The Web2 hardware you have on your desk and in your pocket will not protect your crypto, NFTs and Web3 value.”

My favorite part of this line is the choice of prepositional phrases.

They didn’t use the words “on your computer” and “on your phone.” Those phrases are not intimate enough.

“Buy, HODL and Earn with your LEDGER.”

Buy, HODL, and Earn - classic tricolon.

The word "HODL" is vocabulary invented by accident, started by a crypto enthusiasts who spewed out an unhinged rant after a bad day.

The community seized on the misspelling, and… well, ran with it.

You get it.

In any case, Ledger specifically excludes most readers by deploying a non-word that any knowledgable cryptocurrency participant would understand.

From the world of self-titled digital elites, we move to the world of physical elites.

Here’s an ad for New York’s famed Waldorf Astoria hotel.

First line: “A beacon of timeless glamour.”

We aren’t trying to sell a $97 crypto wallet any more.

We are trying to sell a $1,800,000 piece of real estate.

Different price tier, different product, different language.

We’ve swapped memes for a more exquisite selection of vocabulary. “Beacon,” “timeless” and “glamour.”

These words all have the same meter (stressed-unstressed), giving the opening a sprightly bounce.

“The Towers of the Waldorf Astoria New York has been home to the world’s most fascinating people.”

Each piece of copy is supposed to have one big idea.

At first, I thought the big idea was: “The Waldorf is home.”

After 17 more laps, I realized it’s actually: “The Waldorf is the best.”

That’s why the entire ad dumps a series of superlative adjectives on us, starting with this second sentence. It’s not just “better people” who live here. It’s the “world’s most fascinating people.”

“Live atop the internationally famous hotel, an icon which has set the global standard for hospitality and accommodation since 1931.”

When you are DJ Khaled, you can comes on a hip hop track and say “WE THE BEST.”

When you are the Waldorf, you have to be a bit more artful. You say things like “set the global standard.”

Notice the pretension of “atop” as opposed to “on top of.” You can almost imagine the writer of this ad wearing a monocle and smoking a pipe.

Finally, The 14th Rule is also popping up here to add specificity: The Waldorf has not been around “a while.” It’s been around since 1931. No sooner. No later.

“Enjoy the best of the world’s greatest city and call the most distinguished address and New York home. There is truly no place like it.”

One great way to write a sticky line is to take a common phrase and twist it.

I’m naming this the twisted cliche until an English teacher tells me what it really is.

By separating “home” from it’s red-slippered original phrase in this ad, the reader infers two meanings: that the Waldorf feels like home (meaning it’s comfortable) and that there is no place like it (meaning it's the best).

In this next to last sentence, we also have three superlatives to finish building like a climax.

You aren’t only in the world’s “greatest” city…

you’re experiencing the “best” part of it…

and you have the “most” distinguished address.

And it better live up to the hype. Because…

“New studio to penthouse condominiums residences priced from $1,800,000 – defined by unsurpassed amenities, legendary service, and incomparable history.”

When you try to sell a consumer product via copy, you often want to hide the price until very last minute, after the reader is convinced he needs whatever thingy you are schlepping.

Ledger’s crypto stick eliminated the dollar sign from its ad completely.

The Waldorf proudly displays it.

With only 12 apartments to sell (and a $1B renovation to recoup), no broker can bother to waste her time with floor plan gawkers and open-house crashers.

Basically, if you don’t have $1,800,000 - GTFO.

Then, of course, there is the finishing tricolon. This series of adjectives that are not superlatives, but feel like it:

“Unsurpassed” “and incomparable” are synonyms for “best,” while “legendary” tells us we will find the Waldorf’s service hard to believe.

Here’s something else that’s hard to believe:

Between the two ads, there are only 145 words.

Sometimes, you don’t need an elaborate essay to make your point.

Much love as always <3

-Todd B