The Hypnotic Language of Cult Leaders and Empty Gurus

What Makes Great Writing #025 -- Featuring Dick Van Dyke's grandsons or Katie Silberman or whoever the heck ended up in control of Don't Worry Darling after its chaotic production.

Back in my pre-teen years, I spent a lot of time on my bicycle.

A yard sale Huffy. Originally pink, painted black because I was a boy.

(Certain members of our extended family thought pink wasn’t appropriate for a 12-year-old male, but the joke is on them because pink turns out to be an exquisite match for my skin tone.)

On weekends, I'd hop on my little pink-identifying-as-black bicycle and pedal around the corner, up the hill, and over to my best friend Jacob’s.

Jacob’s house was still under construction when I first visited, but if you climbed up the half-finished stairwell and past the dusty drywall, you’d find it.

An original big screen.

A CRT big screen.

Back then, you could only get a “big” screen in your house one way: hire a couple of guys, pay for their steroid injection, and coax them into hoisting a box the size of four refrigerators into your living room.

This particular big screen was where, flushed with the dopamine of new friendship and pink lemonade, I watched The Goofy Movie for the first time.

Red-headed Roxanne batted black eyelids. Powerline ripped through a series of E naturals in his hit song ("If we lis-ten to each o-ther's hearts"). Bigfoot towered high above my seat on the couch.

Life was joy. No guilt attached.

Probably that’s why, when I rewatched the movie in college in my dorm room alone, I cried. It’s also why I refuse to acknowledge any other Disney movie as “the best.”

Take Moana and Frozen. Keep Aladdin and Nemo. Give me Max and Goofy crossing not only the United States but the impossible chasm between a well-meaning father and his self-seeking son.

The movie is not just a movie to me.

It’s something more.

In his book, What We See When We Read, author Peter Mendelsund points out that we aren’t conscious while reading. We simply remember what we just read, later. In between the reading and the remembering, our beliefs, experiences, personal stories, memories, emotional baggage and so on get attached to the book and change its meaning.

If this is true of a book, it must be doubly true when you add lights and sound and color to stories. Movies, like books, get better or worse after we watch them based on what we remember watching, not what we watched.

When it comes to Olivia Wilde’s thriller — Don’t Worry Darling — many people remember watching a better movie than I did.

They remember the movie for what it represented, not for what it was.

Don't Worry Darling represented the continued crushing of an ignorant belief: that all women belong in a home, shopping and cooking and gossiping.

A good message! But poorly executed.

Somewhere between Dick Van Dyke's grandsons writing the original script for DWD, Katie Silberman revising it, the first leading actor being fired, the second leading actor (maybe?) spitting on another lead actor, and the editors dealing with whatever footage they ended up with, the originality and clarity of the movie’s message were quashed.

It’s too bad.

Instead of dedicating the rest of this post to a thorough bashing of the story (which it deserves), let’s learn instead. What did the movie do really well?

My friend Sophia put it best on Twitter.

Yes! Exactly!

Looking at mostly male dominated self-help communities through a female lens IS a really good idea. The movie fumbled that idea as a whole, but delivered in building a hatable villain, Frank.

Frank, according to Wilde, was based on the "psuedo intellectual, insane man" Jordan Peterson. His speeches show exactly the language used to pull a certain type of person in, and create a slavish devotion.

Let’s look deeper at Frank's first appearance on screen, where he is reassuring the residents of "his world", Victory, they are making the right choice.

(And, yes, calling the town “Victory” is a blatant rip-off of 1984, a much tighter story with an unmistakable moral).

Frank, to a crowd of people:

“What the hell are we doing here?

Why, when this landscape can seem so barren, so hard, so dusty, so... worthless?

Why not? Why not go back to safety? To the status quo? Where it's safe, where we ‘should be?’”

Frank opens with a barrage of rhetorical questions. (Questions that don't expect an answer). The questions build up a juxtaposition (contrasting two elements): hard wasteland vs. comfortable safety.

Juxtaposition is a common tool of the salesman... and the cult leader.

You'll see that come back in a minute.

He then uses the rule of three with concrete adjectives (“barren, hard, dusty”), alongside the repetition of the word "so" before pausing and finishing with an abstract adjective. This last adjective will speak to the men in his audience, as we'll learn in a minute.

(The Rule of Three is huge with screenwriters)

“No. I choose… WE choose to stand our ground. Right?

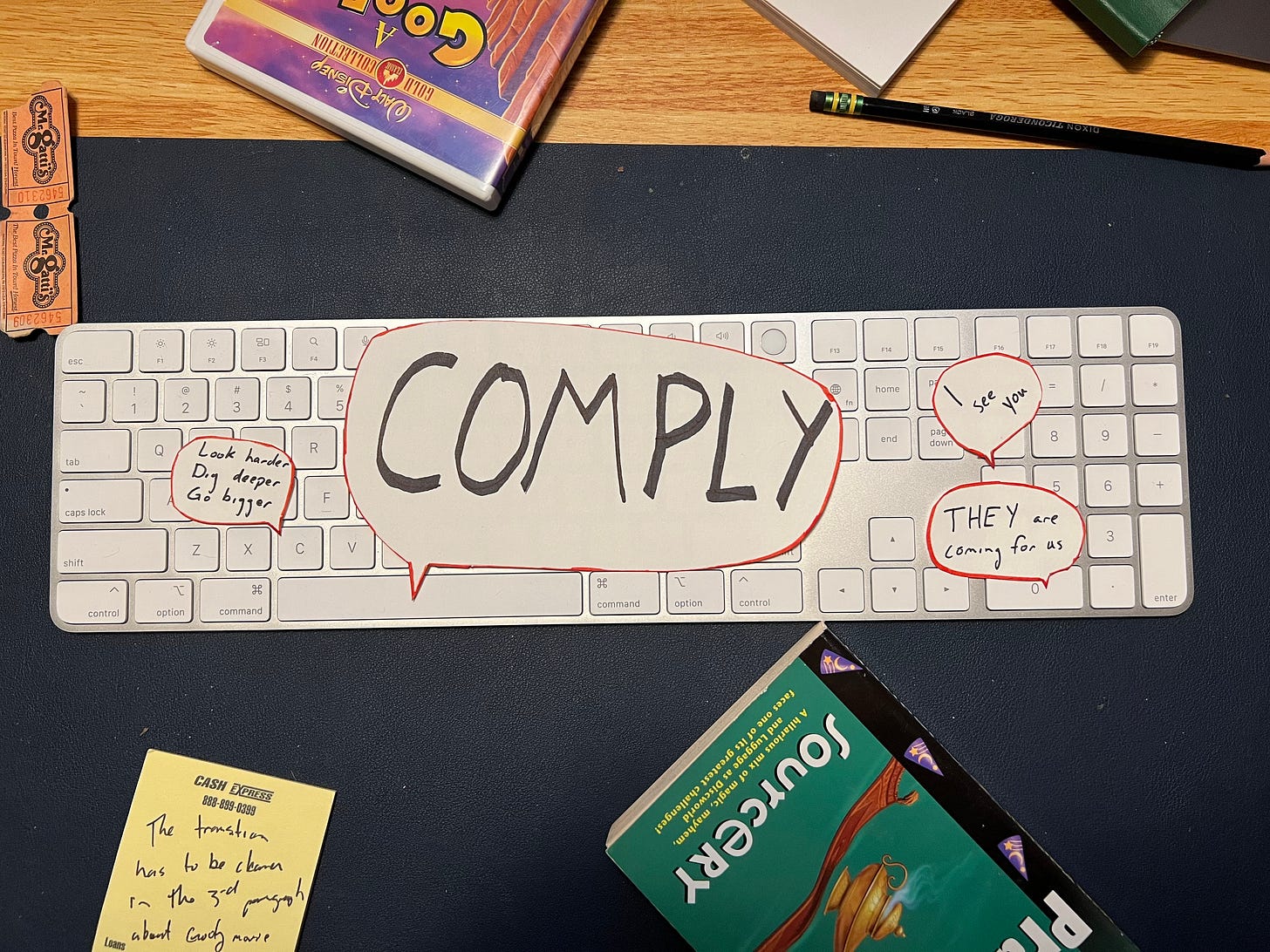

To look harder, to dig deeper. To mine that pure, unbridled potential, that gem of limitless and unimaginable value.”

Whenever an actor — a person who is memorizing and reciting lines verbatim from a script — “corrects” themselves on-screen, it’s a signal to look closer.

Frank first uses a singular personal pronoun (“I”), but then quickly corrects to the plural personal pronoun “we.”

Why? Because when you're leading a cult, you need to imply family, collectiveness, exclusivity at each moment.

Frank's consistently creates an "us versus them" scenario. Although it's unclear who "they" are, that hardly matters to his followers. They are much too busy "looking harder" (at what?) "digging deeper" (to where?) and "mining that pure, unbridled potential (of what?)"

Again we have the rule of three with infinitive + verb:

to look

to dig

to mine

Frank is the worst form of politician. He’s mastered empty rhetoric.

(Good politicians tell better stories than this)

“It's too easy to get distracted by what seems. Much more difficult, braver, I would say to search for what could be.”

There’s a tiny parallel structure here (two phrases with mirrored sentence construction):

“It’s easy to _____”

“(It’s) difficult to_____”

Also - watch that word "brave."

It'll come back.

Frank, to Dean:

“Dean. What is the enemy of progress?”

Dean: “Chaos.”

Frank: “Yes.

Nasty word, chaos. Merciless foe, that chaos. Energy unfocused, innovation hindered, hope strangled, greatness disguised.”

Many times when Frank is speaking to a crowd, he doesn't use full sentences. He simply pours dynamic ingredients into word soup, painting a specific feeling. (Usually terror or ecstasy)

In this case, he creates rhythm using the rule of three once more with nouns and past-tense verbs.

The implication is:

"When you were slaves to chaos...

Energy (was) unfocused

Innovation (was) hindered

Hope (was) strangled

Greatness (was) disguised

By the way, there are four phrases here, not three, but the fourth phrases noun (“greatness”) is grouped with the next sentence:

“I see greatness in each one of you! I know exactly who you are!”

Here, Frank preys on a key insecurity of his followers: they have no real community. They are not known.

He pauses (which is to say, the editor of DWD makes an awkward cut) before performing a little call-and-response with this rapt audience.

Frank: "What are we doing?

Group: "Changing the world"

Frank: "What are we doing?

Group: "Changing the world!"

Frank: “That's right”

What world are we changing? How are we changing it? What's really going on here?

Nobody asks.

Nobody is allowed to ask.

“I look around and I see another reminder of what I'm doing here. Once unfamiliar faces, strangers, one and all, now one brave family...

Adventurers like Bill. Our newest intrepid explorer, this brave young Robinson Crusoe, who's choosing to join us on this adventure. Bill, thank you for being our partner in this.”

Frank has gained an uncomfortable level of devotion from certain members of his community. One way he does this is by singling out some individuals and slighting others.

(This is not presumption. Frank does it every time he is in front of a crowd in the movie).

Notice in this passage the return of the word "brave," twice more, which completes...say it with me... the Rule of Three). And of course, there’s the reinforcement of the juxtaposition here: the isolation of being a stranger versus the comfort of joining a family. (“Once unfamiliar… now family”)

Again, the pronouns speak volume here. Although Frank is taking credit for creating this world (“what I’M doing here”), the return of plural pronouns (“us,” and “our”) ropes in his group again. In this bizarre world of Victory, Frank is our unquestioned leader, but WE are all a family. WE are changing the world. WE are working on important... stuff.

Within Frank's friendly messaging lies a sinister implication.

If "the status quo" takes me down, they're taking you down too.

The story of Don’t Worry Darling is still riddled with unanswerable questions:

Why were the eggs empty? Why is there a plane crash? Why does the ground rumble? Why does Harry float the impossible idea of having a baby? Why are there zombie ballerinas? Why is Florence Pugh getting electroshock therapy... within a simulation? Why does the scenery explode during the climax of the film?

The answer of course is: “um. Because it’s a thriller. Stop asking questions.”

Sigh.

If nothing else, Don't Worry Darling is a reminder (although a very clumsy reminder) for all of us to keep wary of self-help culture (an ecosystem in which I have participated in ways that I am sometimes embarrassed, sometimes proud).

When a person makes a promise, it's up to us to make sure it's not an empty one.

After all, man's reason is his purest and most beautiful bounty, a gift which we should ne'er be quick to dismiss or discard, lest we be suffocated by the quicksand of...

etc etc,

blah blah blah.

Much love as always <3

-Todd B from Tennessee