How a Bumbling Hero Calls for World Peace... Without Feeling Pushy

Great Writing #014 - Featuring Clive Coleman and Richard Bean, screenwriters for The Duke

I quit watching that show Lost long before it ended.

Season 3 did me in. “Not Penny’s Boat.” Ugh.

This sentence was a mystery piled on top of other mysteries like: “who are the others, what is the hatch, why is Hugo still chanting numbers, why can John predict the weather to the minute, and, oh yes, what are they all doing on this island?

Watching Lost felt like work.

Since then, the feeling of overwhelm has only escalated. Friends suggest new shows. They feel like obligations:

“You gotta watch Ozark!”

“You have to see Luther!”

Or it’s a guilt trip:

“You haven’t seen Breaking Bad??”

Television is magnificent. But after recently sloshing through a soapy season 4 of Yellowstone, I can’t help but wonder if we’ve all been tricked into watching 45-hour movies.

This begs the question. Why not just watch a movie?

When you are disappointed by House of Gucci (and you should be), you’ve only lost 2 hours of your life. When you plow through a dull season of Friends, though, you lose 12 hours… and you keep watching (“maybe it’ll get better?”).

The forced brevity of cinema is not only less intrusive, it tends to give us better writing. Ross Douthat pointed out as much in a New York Times piece:

“There are things “The Sopranos” did across its running time, with character development and psychology, that no movie could achieve. But “The Godfather” is still the more perfect work of art.”

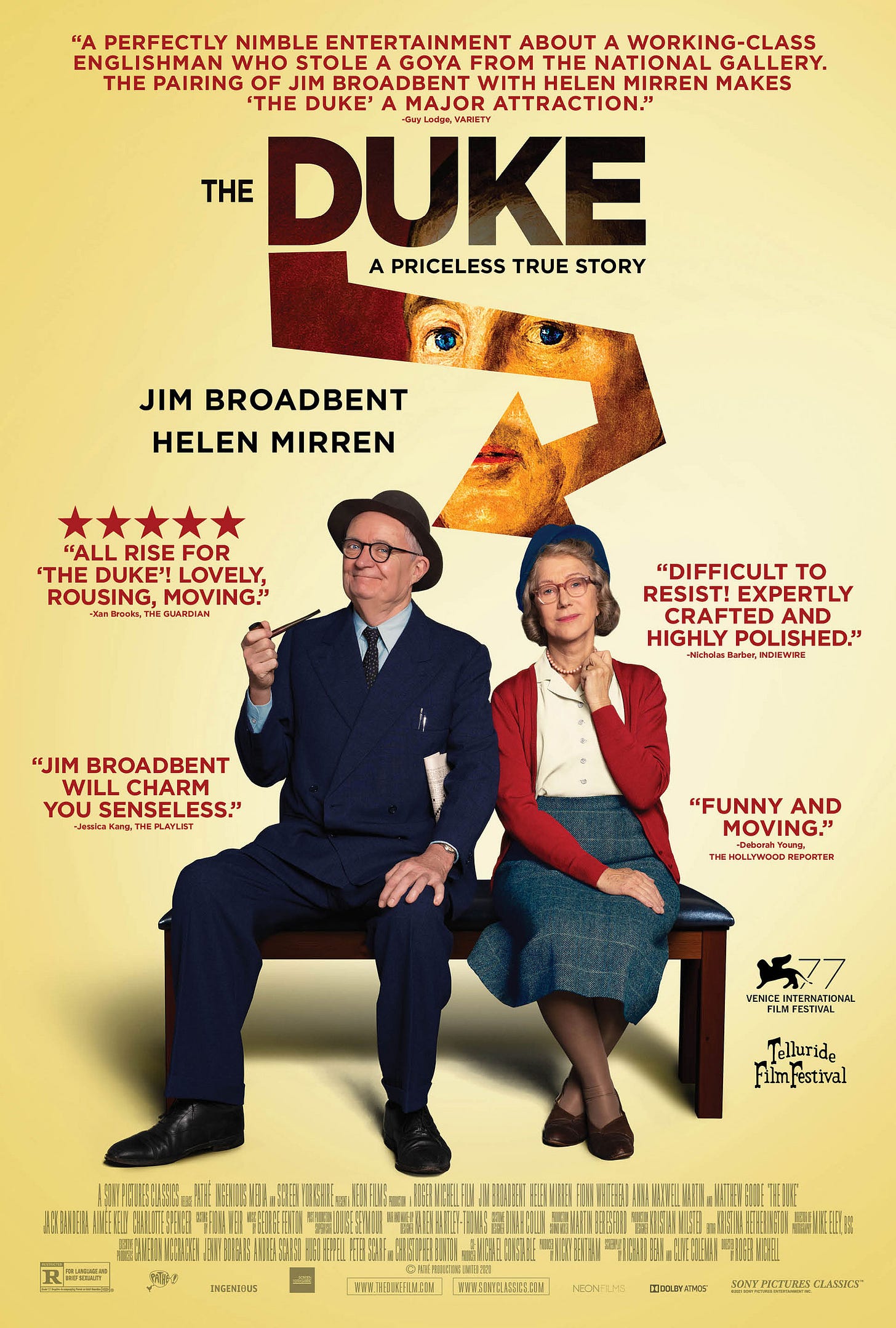

Which brings us to The Duke, a peppy family story about a bumbling do-gooder that ends with a terribly moving speech.

The main character — Kempton Bunton — has been accused of stealing a $140,000 portrait from a national art gallery. Kempton’s lawyer — Jeremy Hutchinson — is asking his client a few questions about the alleged heist.

Then, things take a turn for the amazing.

Let’s take a look.

(Worth noting: Screenwriters Richard Bean and Clive Coleman claim to have gotten several of their lines for the scene you're about to read directly from court transcripts subject himself. A rare feat.)

Writers:

Richard Bean and Clive Coleman

Concepts discussed:

Alliteration: repetition of the same consonant sounds

Ennalage: an intentional grammatical error.

Parallel structure: identical sentence structure repeated in sequence

Hypotaxis and parataxis: essentially, long and short sentences

Diazeugma: a single subject governing multiple verbs

Merism: two contrasting items referring to a whole element

Chiasmus: words, grammatical constructions, or concepts that are used in reverse order

Metaphor: a word or phrase compared to another in a way that is not literal

Anadiplosis: repeating a word at the end of one line or phrase and the beginning of the next

Kempton: “All my life, I’ve been looking out for other people and getting in trouble for it.”

In theory, the coordinating conjunction “and” should not affect how we process the two clauses it connects.

In reality, the word immediately puts us on Kempton's side. Why? Because he sneaks the word "for" (a causal conjunction) into the second clause.

Your brain actually hears this:

"All my life, I've been getting in trouble for looking out for other people."

However, if the line were written this way, Kempton sounds a bit defensive and whiney.

Word choice is important.

Word order is just as powerful.

Jeremy Hutchinson: “When did that start?”

Kempton: “I were about 14. Summer holidays. I’d just finished reading Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. And I felt the need to explore Sunderland"

We open with an ennalage here, using "were" instead of "was." This reinforces the "sweet Kempton" effect.

But I got distracted and found myself on south shields beach. So I got myself in the sea to cool down. A rip tide dragged me out. I was on me own, exhausted, and I knew there was no way I was gonna get back in.

You’ll notice a few sneaky alliterations here:

"South Shields Beach" first. Then toward the end of the sentence come two more: "knew there was no way I was gonna get..."

But I had faith. Not in God, but in people.

Any time you dismiss, doubt, or refute a supreme creator, and you're going to get attention. Amy Sherman-Palladino does this masterfully in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel; Bean and Coleman nail it here.

You can't escape the direct comparison between God and people in this line because of the parallel structure.

"Not in God."

"But in people."

I knew that some nosy bugger would see a pile of clothes on the beach and put 2 and 2 together. So I trusted in that. And waited. Conserved me energy by floatin’, not swimmin’. Looked at the sky. Smile on my face. You could call it trust.

Two elements carry this paragraph.

The first is a balance of hypotaxis and parataxis. Longer lines ("I knew some nosy bugger"... and "conserved me energy...") get interrupted by shorter, punchy ones: ("I trusted in that." “Looked at the sky.")

Musical lines make paragraphs bounce.

The second starring element is a diazeugma. John Wells and Paul Abbot used it in Shameless to turn their drunken main character into a poet; Bean and Coleman use it here to make a homely main character even more understated.

Diazeugma helps you write short lines because you are carrying over the same subject to multiple sentences.

"I looked at the sky with a smile on my face." is grammatically perfect, but rhythmically dull.

An hour later, a lifeboat pulls up alongside and hauls me in. The skipper was a milkman from Blithe. By all accounts a bit of a bastard… excuse my French… but you know, as a milkman, I mean, but there’s good and bad in all of us.

There is a merism hidden in the last sentence: two flip sides of a coin to describe a singular item. Saying “there's good and bad in all of us,” sounds deep, but is a logical head-scratcher. What's left after good and bad?

Merisms often sidestep the black and white parts of our brain. We can’t say they’re wrong because they sound so right.

Now, buckle up. This last part gets heavy.

Kempton — He saved my life that day. Could have been anyone, but I knew someone would. I’m not me without you, do you get me?

Jeremy — We all need each other?

Kempton — No. You are me. It’s you that makes me me, and it’s me that makes you you.

The screenwriters knew that "I'm not me without you" is deeper than it sounds. We would miss it. Lawyer Jeremy interjects his question, opening the door for Kempton's clarifying chiasmus.

"You need me and I need you" is a much different viewpoint than "I'm not me without you."

Jeremy, nodding — Humanity is a collective project.

Kempton — Look, on me own, I’m a single brick. Bit useless. What good is a brick on its ton? But you put a load of bricks together you get a building. You build a building you create a shadow. Already you’ve changed the world.

Kempton backs up his chiasmus with a more familiar narrative device, the metaphor.

Concrete comparisons help bring cloudy concepts into view. By calling humans bricks, we now understand much better.

Within this metaphor, you’ll also spy a small anadiplosis. Bricks make buildings, buildings make shadows, shadows change the world.

Jeremy — your philosophy I think it earns the appellation. How did you apply this thinking to your own struggle?

"Earns the appellation" here simply meaning his line of thinking is justified as a "philosophy."

Now, stop looking for my interjections and read this next passage out loud to yourself. Sink in.

Kempton (thinks) — "You can’t help the dead, but you can be inspired by them. Some of them kids they sent out to France and Belgium came back. They’re over 65 now. Pensioners. Not two pennies to rub together. And isolation... or... not being connected to use the modern lingo, is no way to live a life.

So what you grandly call my philosophy, the "I am you and you are me" thing, tells me that every time someone gets cut off from the rest of us, this nation, this country, becomes a foot shorter.

In Kempton Bunton's day, access to television meant connection to the rest of the world.

Today, it feels like the opposite is true. Expanding media, through the small screen or the smaller one, makes us less connected to one another. And we lose precious souls to depression or anxiety or both. And we surrender our corrupt world to those born into power or money or both.

And we, foot by foot, fall further away from what humanity could be: a collective project in pursuit of peace.

Much love as always,

—Todd B from Tennessee

P.S. I’m reminded of this tweet.

P.P.S. Feel free to watch this scene in full