How One Writer Makes Government Jargon Simple

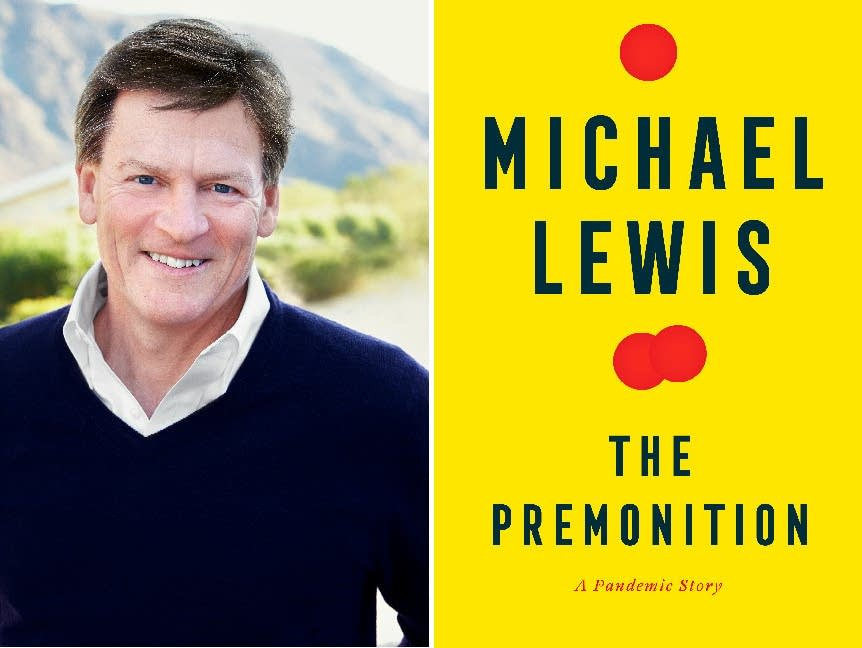

What Makes Great Writing #012 - Featuring Michael Lewis

7 years ago, I heard a quote on a podcast that I would never forget.

“A functional democracy depends on everyone knowing what’s up.”

Most people are aware only that everyone is yelling at each other. However, past the flaming tweets and terrorizing rhetoric, it’s still difficult to figure what, exactly, is happening in our government.

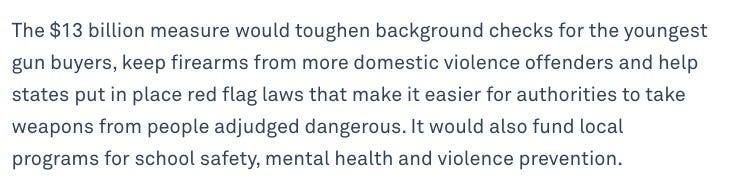

Our bill-writing language could be to blame. Here’s a passage from last week’s bipartisan gun bill.

Now, I’m reasonably well-educated man.

I read and write for a living.

And it still took me roughly a half hour to decode this paragraph.

Inscrutable bills like this send us running to news outlets for a translation. If the Elon-buying-Twitter-fiasco taught us anything, though, it’s that news changes based on where it comes from.

What, exactly, is in the gun law bill?

Let’s see what Breitbart, PBS, and Fox News have to say.

At least these are readable, if all slightly different versions of the truth.

Even if you read every news story to get a balanced view, this still assumes you have more than a passing knowledge of the government’s operation. How does it work? Who is involved? Why does it matter?

What, exactly, goes on at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue?

Questions like this have caused me to dive Michael Lewis’s latest book The Premonition. Michael (known for Moneyball and The Big Short) is a fascinating storyteller who has a unique talent for simplifying complex topics.

Writers like Michael shed a light on the opaque, concealed activity bustling through the White House.

This is the first paragraph of Chapter 4 in The Premonition.

"One day some historian will look back and say how remarkable it was that the strange folk who called themselves "Americans" ever governed themselves at all, given how they went about it."

Explaining a new subject can be difficult. Explaining that same subject to a person who assumes they already know it can be downright impossible.

Instead of describing a problem in the present tense, Michael time travels. It's now 3020. Americans no longer exist. Whatever race exists at that time is studying 2022 America with the same objectivity that we study Ancient Greece now.

With this perspective, we can observe a familiar topic in a new way.

"Inside the United States government were all these little boxes."

The word is "boxes.”

Not "departments” or "institutions," which a politician might use. Not or "units" or "divisions," which an academic might use.

No, the government is made of "boxes."

Concrete. Unmistakeable. Cardboard.

"The boxes had been created to address specific problems as they arose. ‘How to ensure our food is safe to eat,’ for instance, or ‘how to avoid a run on the banks,’ or ‘how to prevent another terrorist attack.’

We understand this concept. A problem arises? Politicians respond with fast action... meaning they create a task force.

They say "we've made a plan to make a plan to solve a problem."

In this metaphor, a new problem equals a new box.

Notice the nifty tricolon of examples at the end. "How to (verb) a (problem).”

"Each box was given to people with knowledge and talent and expertise useful to its assigned problem and, over time, those people created a culture around the problem, distinct from the cultures in the other little boxes."

Let's start this one with the unusual choice. Michael writes "knowledge AND talent AND expertise" instead of "knowledge, talent, and expertise." English teachers would tell you the second option is proper because English teachers are dull people with no room for broken rules.

My guess is that Michael uses the double coordinating conjunction "and" here because he didn't want to add excessive commas.

He's saved those punctuation marks where they are most useful - as an interrupting phrase in the middle of the sentence.

The two commas through your consciousness like javelins.

“…and, over time, those people…”

His interruption is impossible to ignore. Michael points out that although government boxes start out well-meaning, they become something else entirely over time…

"Each box became its own small, frozen world, with little ability to adapt and a little interest in whatever might be going on inside the other boxes."

"Frozen" is an incredible word choice here. Notice that in the previous sentence, the box is in motion. Now, the same box is frozen.

Michael also personifies the box. Can a box adapt on its own? Does it display interest? Of course not. But we know exactly what he means.

And I can't leave this sentence without mentioning the parallelism:

"little ability... little interest"

“People who complained about "government waste" usually fixated on the way is taxpayer money got spent. But here was the real waste. One box might contain a solution to a problem in another box, or the person who my find the solution, and that second box would never know about it.”

Here, the metaphor pays off. By talking about boxes, we can immediately understand the problem Michael wants to bring to our attention in the first place: information doesn't get shared well in the government.

If a congressman were explaining the same issue, it would look something like this:

"Concerning the solution derived from the Committee on Appropriations of the Senate…”

If I were explain it, it would sound like this:

Maybe people have the answers to a better world, but nobody wants to listen.

Much love as always <3

-Todd B from Tennessee

P.S. My cat Pimento Cheese thinks I read too much.