Father Knows Best, but Nancy Myers Knows Better.

What Makes Great Writing? #010 - Featuring Nancy Myers' remake of Father of the Bride

Nancy Myers makes writing look too easy.

Each word is placed slowly and deliberately, as if she’s setting a dinner table for the queen. Whether you’re watching Father of the Bride, The Parent Trap, or The Intern, you’d be hard pressed to find any fat on the dialogue.

Myers isn’t the original creator of FOTB. Screenwriters Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett took a shot at it in 1950. Those two borrowed the content from Edward Streeter’s novel of the same name.

In a way, the long history of this story makes Myers’ work all the more impressive. She didn’t merely modernize the movie to fit the 90s. She sharpened each word. She scrubbed the script until it sang. She made magic, again.

Let’s take a look:

Source - Father of the Bride, 1991, Opening Scene

Writers - Nancy Myers

Rhetorical devices:

Parallel structure: Identical sentence structure repeated in sequence

Diacope: repeating a word after an interruption for emphasis

Hypotaxis and Parataxis: basically, long sentences and short sentences

The 14th Rule: Using a number in order to make a story more believable

Juxtaposition: contrasting two elements or topics to show their differences

“I used to think a wedding was a simple affair.”

Remember last week, when we talked about declarative sentences? Myers implies an enormous transformation with only 3 words.

Maybe she read Joe Karbo’s sales letter too :)

“Boy and girl meet. They fall in love. He buys a ring. She buys a dress. They say I do.”

Gorgeous parallelism. Only one syllable per word, and four words per sentence.

If you say this sequence out loud, you’ll also notice the meter of each line is also the same (stressed, unstressed, unstressed, stressed). Rock your body from side to side while you read the lines.

“I was wrong. That’s getting married. A wedding is an entirely different proposition. I know. I’ve just been through one. Not my own. My daughter’s. Annie Banks MacKenzie… that’s her married name. MacKenzie.”

Ok. A thick one here.

The last sentence here is an elaborative diacope, a device Myers’ will roll out twice more in this monologue. The main character, Mr. Banks, repeats the word “MacKenzie,” after adding context, stressing that this is not his beloved daughter’s given last name.

It’s also worth pointing out the stilted, parataxic language. It’s as if Mr. Banks can hardly bear to say more than 5 words at a time. The longest sentence to this point is only 10 words.

Contrast this with the opening of The Holiday, which Nancy Myers also wrote. Kate Winslet’s lines are much longer because that character is a harried newspaper reporter, not an exhausted dad.

Every character has a different style.

“I’ll be honest with you. When I bought this house 17 years ago, it cost less than this blessed event in which Annie Banks became Annie Banks MacKenzie.”

Notice this weird line: “I’ll be honest with you.” Why wouldn’t Banks be honest with us? These 5 words aren’t meant to convince us of Banks’s integrity, but to allow Banks himself to be more conversational.

The 14th Rule is at work here as well: It wasn’t “many years” ago that Banks bought the house. It was “17 years” ago.

We’re lengthening the sentences a little. Mr. Banks is settling in, or so it seems…

”I’m told that one day I’ll look back at all this with great affection and nostalgia.

I hope so.”

The sharp contrast of hypotaxis to parataxis here is exquisite. Banks blows up and then popping the balloon.

“You fathers will understand. You have a little girl. An adorable little girl who looks up to you and adores you in a way you could have never imagined.”

Another elaborative diacope here. Young Annie was not just a little girl, but an adorable one.

“I remember how her little hand used to fit inside mine. How she used to love to sit in my lap and lean her head against my chest. She said I was her hero. Then the day comes when she wants to get her ears pierced, and wants you to drop her off a block before the movie theatre. Next thing you know, she’s wearing eye shadow and high heels.”

Great writers can show you the passage of time without ever mentioning a date.

Myers shows two pictures of Annie: A little hand inside her father’s. A little head on his chest. Then, the pierced ears, the movie theaters.

She shows passage of time by using a tool called juxtaposition, contrasting the closeness of a toddler with the distance of a teenager.

“From that moment on, you’re in a constant state of panic. You’re worried about her going out with the wrong kind of guys, the kind of guys who only want one thing. And you know exactly what that one thing is because it’s exactly the thing that you wanted when you were their age.”

Another elaborative diacope here. Repeating “kind of guys” to elaborate which kind of wrong guys we’re talking about here.

“Then, she gets a little older, and you quit worrying about her meeting the wrong guy, and you worry about her meeting the right guy.”

The nifty parallel structure here:

“worrying about her meeting the wrong guy.”

“worry about her meeting the right guy.”

“And that’s the biggest fear of all because then you lose her. And before you know it, you’re sitting all alone in a big empty house with rice on your tux wondering what happened to your life.”

The two gerund phrases at the end here are haunting: You aren’t just sitting. You’re doing so all alone. You’re doing so in a big empty house. You’re doing so with rice on your tux.

And you aren’t just “wondering.” You’re wondering what happened to your life.

Thanks to some Nancy Myers magic, we are now primed to watch the 105-minute journey that Mr. Banks will take from comfort to chaos, from grouchy to grateful, as an ordinary man realizes that losing his precious daughter means surrendering a chunk of his own soul.

If you’ve got some time this weekend, rewatch the whole movie.

It’s worth the time.

Much love as always <3

-Todd B

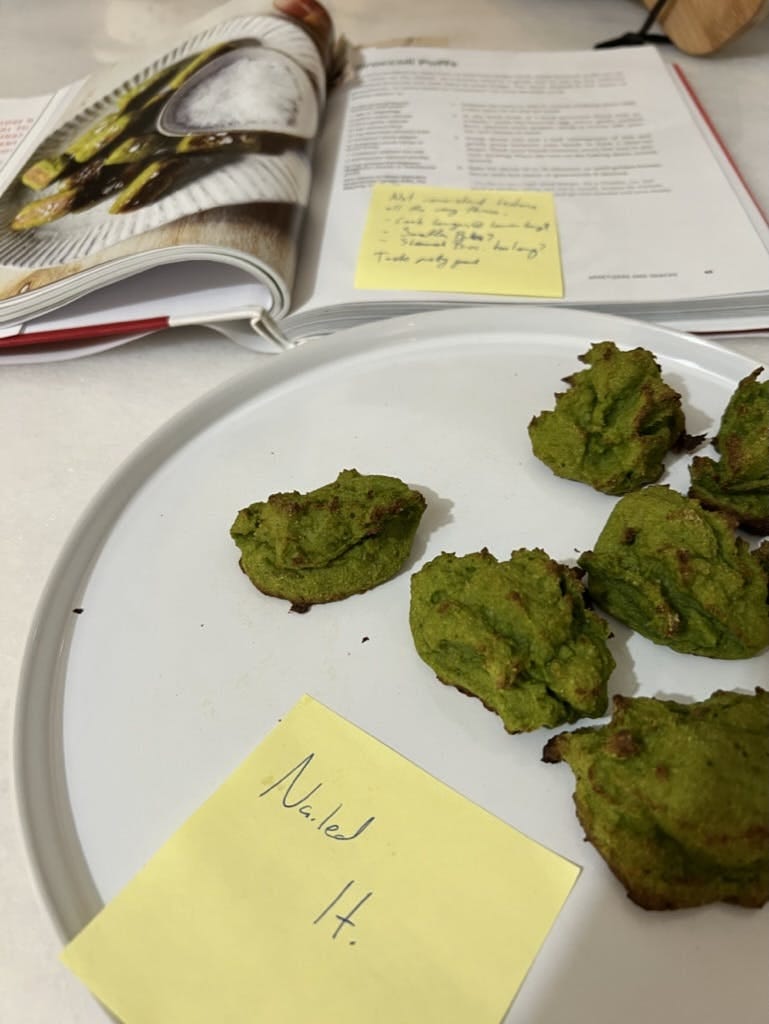

P.S. This week I made broccoli puffs… or green play doh. Taste was 9/10 but shape was -3/10