Stop Trying to Be a Great Writer

And focus on the principles of great writing instead.

Most writing advice is self-help in disguise.

Ten minutes online would tell you the task of writing is not to fiddle about with adjectives for ages, but to simply believe a book into being.

You can’t blame the internet for this. It started much earlier:

“Sit down at a typewriter and bleed” — Ernest Hemmingway

“The worst enemy to creativity is self-doubt.” — Sylvia Plath

“A professional writer is an amateur who didn’t quit” — Richard Bach

These are hopeful words.

Useless too.

Great writing is hard to do. It might be impossible to teach. That’s why, when asked for advice, even great writers spew out generic platitudes that confirm our desire to be a “good writer,” a “real writer,” or maybe — if we work hard enough — the “best writer.”

The problem is, even those who have been deemed as great writers still have to sit down and do great writing. Papa Hemmingway himself rewrote the start of Farewell to Arms 50 times.

Luckily, great writing is not about hacks or tricks.

Just principles.

Humanity’s love of literature has defined and refined the principles of good writing over the years. The topic is endless (thus, this newsletter), but for today, we’ll focus on three elements:

Purpose

Audience

Stance

Good writing has a clear purpose

First, keep this in mind: It’s very possible that you won’t know your purpose when you start writing.

Writing itself is an exercise of inquiry, an excuse to research and answer questions you’ve wondered about.

Sure, freaks of nature like Nick Wolny can choose a topic, write a flawless draft, and then still have time afterward to go be gorgeous somewhere. If you aren’t one of those (I’m not), you’ll likely have to depend on something like stream-of-consciousness writing to get started.

After you’ve written a draft, though, getting clear on your purpose helps you refine and sharpen the remaining drafts for maximum impact.

Your purpose doesn’t have to be life-changing or grand.

It just has to be clear.

Typically, the purpose of most writing falls under one of the following:

To deliver the facts of an event

To persuade someone of an idea

To curate helpful or entertaining information

If you write online independently, you probably don’t have to worry much about delivering facts. Your time will likely be spend persuading and/or curating for an audience.

When persuading, I like to use an exercise in my friend Joel Schwartzberg’s book, Get to the Point.

It’s called the “I Believe Test.”

“The [I Believe Test] is a pass or fail test, and it boils down to this.

Can your purpose fit into this phrase to form a complete sentence: “I believe that ______.”

Maybe you’re writing about equal work for equal pay. Your purpose probably wouldn’t be “I believe equal pay,” but it might be “I believe women are significantly underpaid.”

Your purpose, then, is to convince me of what you believe.

For curated ideas, your purpose is probably some version of collecting useful or unusual ways for a group of people to improve their lives. In order to do that successfully, knowing your audience is critical.

Good writing has a clear audience

Your audience determines what you say. More importantly, it determines what you don’t say.

Most of the time (and especially on the internet) a goal of writing is brevity. You will have to make choices about which words belong and which don’t.

What needs more explanation?

What needs less?

The better you understand your audience, the easier it is to answer these questions.

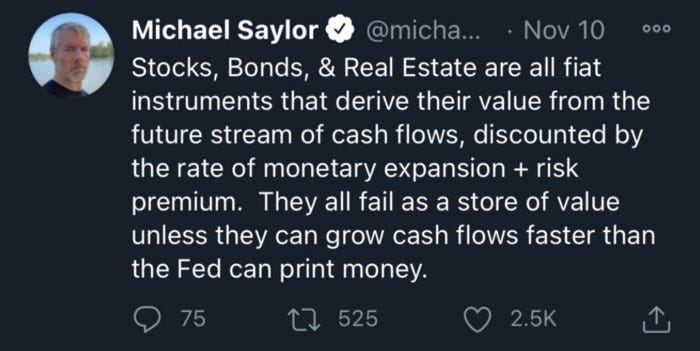

Take, for example, this 2-year-old tweet I can’t seem to forget.

If you’re anything like me, you probably looked at this and thought — Huh?

Saylor didn’t have the average person in mind when he wrote that tweet. But at least one person who read the tweet did:

Thanks to his career in finance, Tim can help average people understand money. In order to do so, he often has to use basic explanations before diving into the topic at hand.

So, he took 2,420 words to explain the same idea Saylor only used 49 to approach.

Both pieces of writing had the same purpose, but not the same audience.

Both pieces went viral thanks to that clarity.

That’s the power of knowing your audience.

Good writing has a clear stance

Your purpose reveals what you want to say.

Your audience represents who you want to say it to.

Your stance shows how you want to be seen saying it.

Your stance is how you feel. It’s your attitude.

But these are words on a page. You don’t have vocal tone or body language. How on earth do you show emotion?

Let’s look to The Norton Field Guide to Writing:

“Tone is created through the words you use and the way you approach your subject and audience.”

To show how this works, take a look at two examples of posts with a similar purpose and audience, but with drastically different stances. Sunil Rajaraman and Taylor Gordon are two authors who have tackled the topic of entrepreneurial FOMO.

Look at their first two lines (profanity blanked out by me).

“Artificial Intelligence. If you hear those two words again, you are going to throw your f**king computer out the window.”

Everybody’s Rich But You — Sunil Rajaraman

“FOMO can happen in your personal life, and it’s a real phenomenon in business as well. It seems like every day there’s a new business fad that’s being touted as the next big thing to make you a gazillion dollars.”

How to Not Fall Victim to Business FOMO — Taylor Gordon

Immediately, it’s obvious that Rajaraman is taking a direct, commanding approach, and Gordon is moving toward a more academic, calm piece of writing.

Each carries his stance throughout the piece, with the former using a fake narrative as a vehicle for his withering sarcasm, and the latter writing only in practical, real terms.

The same stance, repeated over time and carried across different topics, can become your writing voice. Rajaraman takes the same stance when describing the trials of COVID lockdown in Silicon Valley. Gordon repeats hers when giving advice about cold pitches.

To oversimplify, your stance is who you are.

Though we may forever be in pursuit of that elusive good writer title, it’s important to the following in mind:

Every piece of writing demands that you follow the process. No matter how many awards you’ve won, books you’ve written, or followers you have, each blank page is a brand new challenge.

Thank God for that.

I would add one more reason a writer does write; (maybe it’s two reasons, but I believe it’s one in the same) 4. To feel and to heal

Life is a brutal test of courage and fortitude if nothing else, and writing is a blessed balm for both writers and readers alike. I think the ages attest to this phenomenon.

I need to expand my idea of what a writer is. I have it in my mind that only authors of books are writers and everyone else are amateurs. I grew up surrounded by books - they were my refuge. It's hard to let go of an idea that has brought me so much comfort over the years.