Use "The Kite Structure" to Save Dull Topics

What Makes Great Writing #027: Featuring Matthew Shaer's NYT Piece on... Cardboard???

Last week’s free webinar was fun. (And only a SLIGHT disaster)

So, I’m doing it again.

This week’s session is called: Double Your Writing Impact Without Posting Twice as Much

(No, it’s not about simply “marketing more”)

Click that blue button to register

Whenever I am a wrinkled pre-corpse, and whenever my family gathers around to say goodbye, and whenever my great-grandson floats over on his hoverboard and asks: “was he ever cool?”, his mother will be forced to answer:

“No honey. He was never cool.”

Then, their robot assistant will pull up a record of my life, revealing the countless hours spent obsessing over things like book dedications and sweater descriptions.

Or in this case: cardboard.

The article we're looking at today isn't really about cardboard, of course, and the lesson we’ll learn is applicable to any topic you wish to write about. Still, cardboard feels niche. And as The LCD Theory of the Internet states, the more niche your topic, the fewer people will care.

The goal of writing about such topics is not necessary to make EVERYONE care about them (they won’t). The goals are:

to satisfy the enthusiasts, and

intrigue those who COULD be enthusiasts.

“Where Does All the Cardboard Come From?” is 5,500+ words long. How do you write that many words, with that much nuance, about that dull a topic, in a way anyone can digest?

In other words: how do you structure the piece?

During the year of running this publication, I’ve avoided structure completely. “Structure” reminds me of “templates.” Templates turn off creative brains. Dead creative brains lead to a flood of copycat writers. (You’ve probably seen it).

Good templates or structures are:

specific enough to be helpful

broad enough to force thought.

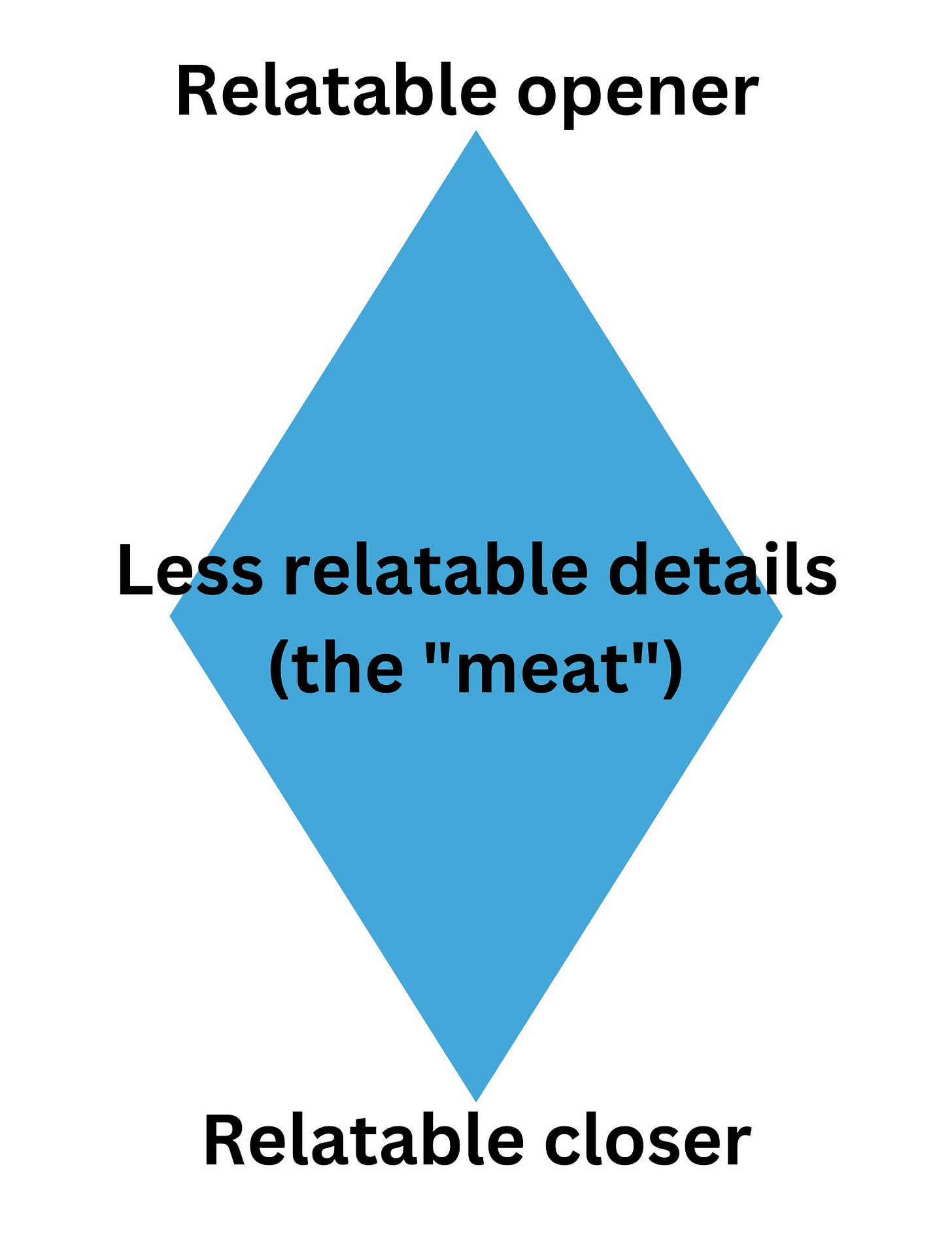

Matthew's Shaer piece uses The Kite Structure.

The kite structure starts with words most can understand before pulling the reader deeper into more complex ideas. Finally, it winds back down to a closer that makes perfect sense to the reader.

This describes the format AND content, by the way. The beginning and ends of a kite-structured article are easy to read (semantically) and easy to comprehend (conceptually).

Let's see how Matt does it:

Part 1: Relatable opener (here, a story)

Opening line: "Before it was the cardboard on your doorstep, it was coarse brown paper, and before it was paper, it was a river of hot pulp, and before it was a river, it was a tree."

Matt moves quickly, literally tracing cardboard from your doorstep to a tree, the raw material of cardboard.

(Regulars of this publication should spot at least 2 rhetorical devices. I won't unpack them today.)

Matt is telling a story, the easiest opener to follow. There are also no abstract nouns here. We go from cardboard to paper to pulp to river to tree. Later, we will go from car to forest to factory, and we’ll quickly realize how much freaking cardboard there is to go around here.

Part 2: Adding less relatable “meat” (here, the economic impact)

Opening line: “Most of us have a relationship with cardboard that ranges, depending on the day and our Amazon Prime membership status, from reluctantly reliant to fully subservient.”

Notice the deliberate plural pronoun chosen here. “Us.” Cardboard nation includes you. It’s not some foreign idea.

(That'll be important shortly).

Matt compares the brown stuff to "millions of miles of highway" and "16,000 aircraft carriers." Along the way, he is revealing a web of capitalist desires and their consequences

I'm not guessing. The ending line shows us Matt's opinion about this. This is likely his whole reason for writing, and since you have mentally agreed that you have a "relationship with cardboard," this passage will land.

"It reminds us, if we care enough to dwell on it, what the box boom is really about, which is capitalism and buying lots of stuff and above all, instant gratification — even if that gratification involves a bottle of conditioner shipped through three ports, one fulfillment center and hundreds of miles of highway."

Phew.

Part 3: The least relatable, “meaty-est meat” (here, the history of cardboard)

Opening line: Given its symbiotic relationship with commerce, it should be no surprise that the progenitor of the mass-produced cardboard box, a Scottish émigré named Robert Gair, was himself a manufacturer.

This is an interesting start to a story. Why is it tucked in the middle?

Answer: Without context, very few people would care about the historical impact of cardboard, no matter how neat the story.

The middle of the kite structure is the place to leave your heaviest load. Some enthusiasts will gladly devour the nuance. Others (like me) will keep reading ONLY because we've come this far, and feel compelled to finish.

Once you’ve firmly planted the hook, you can ditch the internal cliffhangers.

Part 4: Returning to the relatable (here, the ecological impact)

Opening line: "Last year, 5 percent of the plastic waste consumed in the United States was recycled back into plastic; the remainder was deposited in landfills around the country, where it is almost certainly still moldering today."

We have now moved OUT of abstract economic calculations and historical recollection, and into a topic we can understand.

Throughout this section, Matt inserts a fascinating interview with "cardboard innovators" (hilarious). He also drops details on cardboard’s future, hinting that it could replace beer cans and other aluminum containers.

(Dropping toward the bottom of that kite).

Part 5 - Relatable closer (here, a prediction of cardboard’s future)

Opening line: "Late last year, International Paper announced it would build a new plant in Atglen, Pa., a town about an hour’s drive west of Philadelphia."

We're back in the U.S. Soon, we will be back in a forest, where this article began. (and all my "Hero's Journey" fans cheered.)

Matt brings home this winding piece with a glimpse into the future of cardboard. The odds point to us swimming through an ocean of the stuff. This idea is driven in like a spike with the final few sentences.

"The forest closed around us; a deer shuddered through the undergrowth. A red squirrel stared back at us from a mound of loam.

But mostly it was just pines, pines, as far as the eye could see."

Many elements of great writing are exciting. Fancy Latin names, shocking comparisons, unforgettable imagery.

A less sexy, more critical element of great writing is organization.

Sounds dull. Imagine, though, a filing cabinet without files. A mound of laundry with no baskets to sort sheets, shirts, and underwear. A bookshelf without shelves.

For the reader, good structure is a path of breadcrumbs to be gobbled up and enjoyed.

For the writer, good structure makes writing a draft easy.

Well. Easy-ER.

Much love as always,

-Todd B from Tennessee